CON law elimination sets off inpatient rehab rush in Florida

Back to physical health resource hub

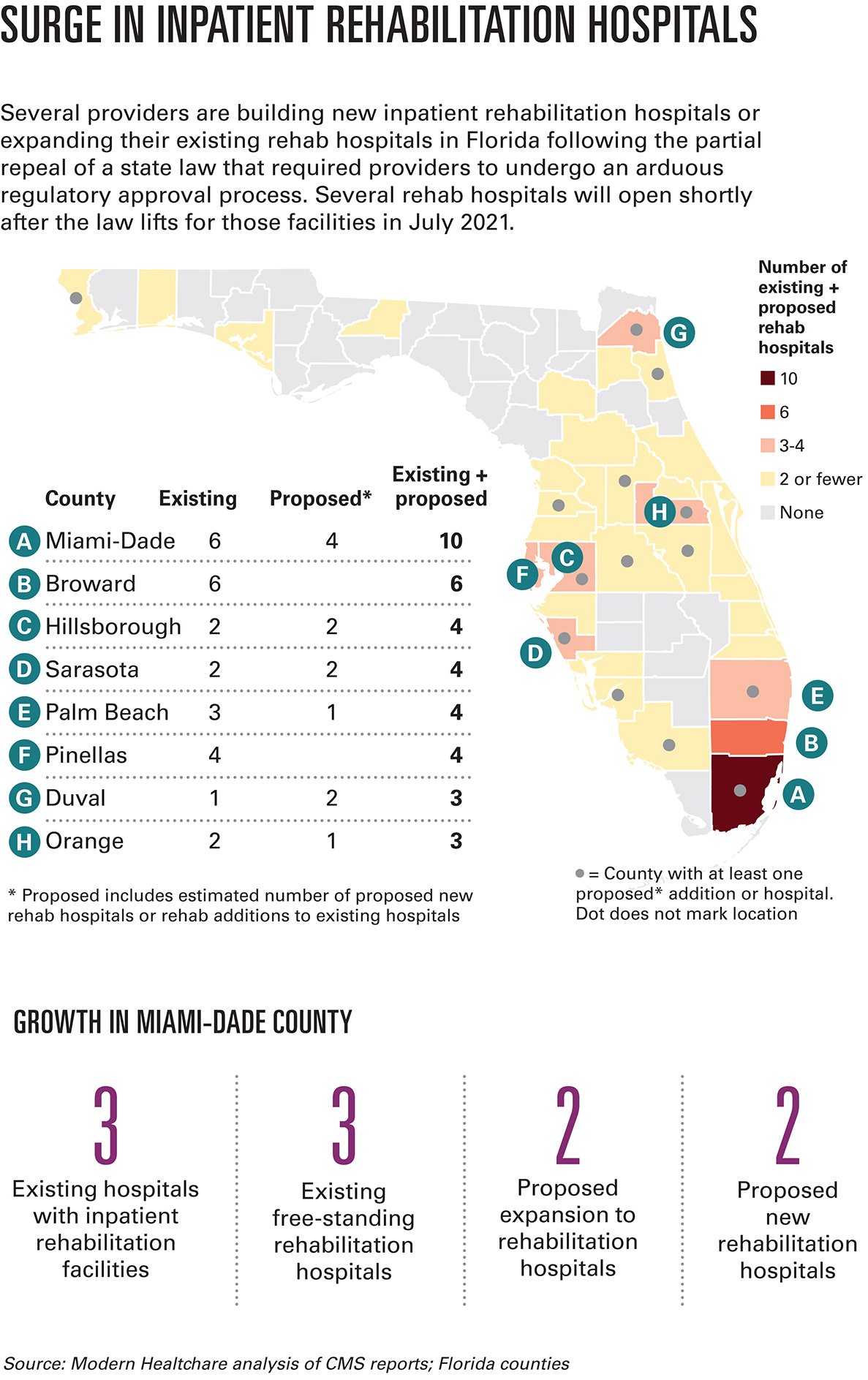

A number of healthcare providers are adding more inpatient rehabilitation hospitals in Florida following the state’s certificate-of-need law repeal. Some experts worry the trend will push healthcare costs even higher.

The CEO of Florida’s BayCare is fielding more pitches than ever to form joint ventures around newly built inpatient rehabilitation facilities.

The answer is always no.

“If I own half of it, I have an economic incentive to keep it full,” said Tommy Inzina. “I have to get everybody I can justify putting in there, in there.”

That’s the opposite of BayCare’s strategy. The not-for-profit integrated system, with 15 acute-care hospitals in Tampa Bay and West Central Florida, is on the hook for roughly 270,000 at-risk health plan members, so the goal is to keep costs low. Inpatient rehab, used by patients recovering from hospitalizations for serious events like strokes, car accidents or amputations, is among the most expensive medical settings. It’s also one of the most profitable.

The rush to build was set off when Florida lawmakers significantly deregulated the hospital industry in 2019 by eliminating the requirement that the state determine whether there’s enough demand for the services they’re looking to add. The so-called certificate-of-need process often took years and could cost millions to litigate.

With that roadblock gone, several health systems have restarted planning or begun construction on acute-care hospitals and other projects that had been held up in litigation or that the state may not have approved under the previous rules.

Florida is among several states that have partially or fully repealed their CON laws. Nursing homes and hospice providers in the state still need CON approval before adding facilities. As of late 2019, 35 states and Washington, D.C., still had some form of a CON program, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Pre-construction

When the deregulation takes effect for inpatient rehabilitation in July, construction or planning will already be underway on over a dozen such facilities. By the end of 2023, the state will have well over 800 new inpatient rehabilitation beds.

“They’re trying to align construction so they can open quickly after CON goes away,” said Tom Mullin, executive vice president of hospital operations for Select Medical Corp., a rehab provider that’s taking a measured approach to expansion in Florida.

The state’s hospital operators are split on the polarizing topic of the partial CON repeal. While providers share the stated goal of lowering healthcare costs, they have dramatically different views on how to get there.

Encompass Health is building more than anyone, with eight inpatient rehab hospitals announced plus expansion of an existing facility. HCA Healthcare is spending up to $300 million on inpatient rehab in Florida, with at least three new facilities and an expansion underway. Officials from both for-profit chains declined to discuss their plans.

Select Medical, also a for-profit provider, is adding 30 beds to its inpatient rehab facility in Miami that are expected to open in the second half of 2021, and Mullin said multiple other projects are still in the due diligence phase.

“With CON repeal, I do think that we’ll see many more in the future,” he said.

It’s not surprising that investor-owned providers see promise in inpatient rehab. Not only is demand for the service projected to rise nationwide and especially in Florida, it’s more profitable than treating patients in acute-care hospitals. Traditional inpatient care is projected to generate an aggregate Medicare margin of -6% this year, per a recent Medicare Payment Advisory Commission report. Compare that with free-standing inpatient rehabilitation facilities, which generated 40% Medicare margins in 2019. Inpatient rehab services run by hospitals generated a 19% margin that year, the report found.

BayCare’s Inzina and others are concerned that the outcropping of new inpatient rehab facilities across the state could prompt a spike in healthcare costs if patients are disproportionately treated there when they could be cared for in less expensive settings, like home care or outpatient physical therapy.

Big Plans for Rehab Growth

HCA Healthcare

HCA isn’t shy about its aggressive growth strategy for Florida.

Sam Hazen, CEO of the massive, 186-hospital company with north of $50 billion in annual revenue, said on a February investor call that the company has committed significant capital to develop new and expanded inpatient rehab capacity in Florida following the state’s partial certificate of need repeal. HCA, based in Nashville, is far and away the country’s most profitable hospital chain, having made almost $4 billion in profit in 2020 despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hazen offered more detail on an April investor call, noting that the company discharges hundreds of thousands of patients into post-acute settings, and would prefer to keep them in-house.

“Because of the CON relaxation in Florida, we have made a large commitment to inpatient rehabilitation facilities in the state of Florida, where we have the greatest opportunity to do the same thing with rehab,” he said, adding that the company is investing up to $300 million on inpatient rehab in the state.

Encompass Health

While a much smaller company than HCA, with less than $5 billion in annual revenue, Birmingham, Ala.-based Encompass has been on a similar growth trajectory in Florida as HCA. It has 12 hospitals and 983 licensed beds in Florida, its largest state behind Texas.

Encompass has eight more hospitals in the works, plus one expansion. In prior years, Encompass would add about two hospitals per year in Florida, Southeast Region President Linda Wilder said in a September 2020 promotional video on the company’s website.

“The old rules have changed, and we basically just expedited our long-term plan,” she said.

Select Medical Corp.

So far, only two of Select Medical’s 30 inpatient rehab facilities are in Florida, but Tom Mullin, its executive vice president of hospital operations, said that number is set to grow.

Select is adding 30 beds to its Miami inpatient rehab facility that are expected to come online in the second half of 2021, and Mullin said multiple other projects are still in the due diligence phase.

“With CON repeal, I do think that we’ll see many more in the future,” he said.

While Select could stand up its own rehab hospitals like Encompass does, Mullin said the company instead prefers to partner with health systems. It’s a slower approach, but it ultimately means the facility will have a steady flow of demand and access to physicians.

Philosophical differences

The effects of Florida’s partial CON repeal have yet to fully play out, and opinions are across the board on what they’ll ultimately be.

Those supporting the repeal argue it will increase competition and push out expensive, low-quality providers, lowering prices.

“The free market should determine whether there should be a hospital or not,” said former Florida state Sen. Ray Rodrigues, a Republican, who helped pass the CON repeal legislation.

Opponents of repeal worry that powerful companies with money to spend will build duplicative services in excess of demand, which drives up costs.

If Miami is any indication, the rest of the state could be headed toward higher costs, said Steven Ullmann, director of the University of Miami’s Center for Health Management and Policy.

The Miami market has a long-standing reputation for having extraordinarily high healthcare costs, partly the product of an overcapitalized market. Miami had among the country’s highest Medicare spending of any region in the U.S., according to the latest Dartmouth Atlas data, and it has floated at or near the top for more than a decade.

South Florida is a hyperactive market, with providers putting up expensive facilities and equipment in an attempt to outdo their competition. That in turn drives them to perform lots of procedures—some of questionable necessity—to cover those costs, Ullmann said.

“With technology and competition, prices don’t go down, they go up and utilization goes up,” he said.

Go it alone or form joint venture?

As health systems like BayCare consider inquiries from rehab providers looking to partner, they must decide whether it makes more sense to join up or go it alone. There are pros and cons of both.

Hospitals are increasingly on the hook for the total cost of patients’ care under Medicare bundled-payment programs or Medicare Advantage plans. In that environment, executives said they prefer to have ownership over all aspects of their treatment, including—if necessary—inpatient rehab.

“To be able to do that in a continuum of which you have complete control is a potentially even more reliable way to ensure, first and foremost, optimized care for every single patient,” said Tom VanOsdol, CEO of Ascension Florida and Gulf Coast. “And secondarily, optimized performance under any episode-based payment methodology.”

Ascension Florida and Gulf Coast is also taking calls from rehab providers about joint ventures. The system doesn’t currently offer inpatient rehab, and VanOsdol said they’re actively considering the best way to add it. It’ll likely make more sense to insource, especially because the health system participates in iterations of Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement program and its Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model, he said.

For their part, rehab providers argue that outsourcing to them and succeeding under value-based contracts aren’t mutually exclusive.

Bundled payments are easy to manage under established partnerships with rehab providers, said Mullin, of Select Medical. Hospitals can easily track patients’ progress. If there’s not a relationship, it can be difficult to transfer patients to rehab in a timely manner, potentially resulting in costly delays, he said.

Orlando Health, a 10-hospital system that’s growing rapidly, with $1 billion in active construction projects, is yet another system looking to grow its inpatient rehab offerings. It already has a 53-bed unit at one of its Orlando hospitals, but is assessing where to expand and by how much, said Matt Taylor, Orlando Health’s vice president of asset strategy.

It may make sense for Orlando Health to partner with a provider that’s solely focused on inpatient rehab, Taylor said. The system has already entered joint ventures on home care, urgent care and hospice services.

“You might want to think about, ‘Can we do this better, faster, cheaper and for higher quality by partnering with someone that only does this?’ ” Taylor said.

But increased participation in value-based payment could also mean providers have incentives to keep patients out of expensive inpatient rehab facilities if it’s not entirely necessary. They might instead refer patients to home care or outpatient physical therapy.

“If that plays out, Florida will soon have an overcapacity of inpatient rehab beds, given all the construction underway,” said Doug Baer, CEO of Brooks Rehabilitation, a not-for-profit rehab provider based in Jacksonville. “That said, Florida’s rapidly growing population is adding demand,” he said.

“The more prevalent those models are, I think some of the utilization of higher-cost facilities—which are inpatient facilities—are not as much,” Baer said.

Nathan Carroll, assistant professor of health services administration at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, was among the healthcare experts who predicted that scenario. But the results of his 2019 study suggest that participation in Medicare’s BPCI program doesn’t make hospitals any less likely to refer patients to their own inpatient rehab.

“What it suggests to me is that maybe the financial incentive under the bundled-payment program isn’t stronger than the financial return for treating patients at the inpatient rehab that you own,” Carroll said.

Carroll’s study also found that Medicare paid more for hospitalizations—inpatient and post-acute combined—in cases where hospitals owned inpatient rehab compared with when they owned skilled-nursing facilities and home health services.

If those results hold true in Florida, the federal government can expect to spend more on care when the new inpatient rehab facilities come online, Carroll said.

“Post-acute is a big concern with respect to controlling the overall Medicare budget,” he said.

Growing pains?

All the growth among the for-profit companies has smaller, not-for-profit health systems and rehab providers concerned. They worry that those well-capitalized, investor-owned providers will siphon off commercially insured patients, leaving them with a disproportionately high share of uninsured and underinsured patients.

“We think it’s critically important that the safety-net providers are protected,” said Jason Barrett, CEO of Flagler Health+, a single-hospital system in St. Augustine, Fla. “Because as you see this cannibalization of these systems going into areas that have better economics, it does affect safety-net providers in continuing to serve their mission.”

Barrett added that for-profit providers tend to locate their facilities in affluent areas where patients are more likely to have private insurance.

“There’s also the question of whether uninsured patients or those on Medicaid will be able to easily access inpatient rehab,” said Baer of Brooks Rehabilitation.

One effect of Florida’s partial CON repeal is certain: Healthcare providers are spending a lot less time and money making their cases before the state’s healthcare facility licensing body, the Agency for Health Care Administration. The agency rejected more than one-third of CON applications between February 2017 and February 2019, according to an analysis by the law firm Hall Render.

It wasn’t just AHCA that made the process tough. CON was combative, with providers regularly sending lawyers and consultants to their competitors’ hearings to try and derail their projects. Even if they were approved, competitors could file appeals, triggering costly litigation that lasted years.

BayCare’s Inzina, for example, said if another provider had applied to build a hospital near one of his, he would have appealed.

“I would likely keep appealing for no reason other than to delay it,” he said. “Every year I delay it is another year I can operate without having a competitor there.”

The dynamic created a “cottage industry” of lawyers, consultants, finance folks and expert witnesses, said Gary Davis, a partner in McDermott Will & Emery’s healthcare group.

Encompass and HCA have themselves been CON rivals. In one case, Seann Frazier, a partner at Parker, Hudson, Rainer & Dobbs in Tallahassee, represented Encompass in opposing an HCA rehab facility in Brooksville, Fla. Frazier argued that HCA has made a concerted effort to expand its inpatient rehab programs to “promote corporate profitability,” even when there’s no community need. The state approved the facility in 2019.

In another case, HCA asserted there was “insufficient need” for Encompass’ proposed 50-bed rehab facility in Hillsborough County. The state also green-lighted that project in 2019.

Rehab providers are concerned that if hospitals increasingly build their own rehab facilities, they’ll stop referring to stand-alone rehab providers, said L. Pahl Zinn, an attorney with Dickinson Wright.

Therein lies a tricky balance for hospital operators. The Affordable Care Act encouraged a focus on patient outcomes and lower costs, both of which are improved through care coordination. But they also must be careful not to potentially violate antitrust laws.

“You want to achieve a balance between the providers coordinating their services, but also only to the extent it doesn’t result in market dominance,” Zinn said.